LOS ANGELES — Stefan Simchowitz knows who he is. He’s an art collector, art dealer, and art advisor. But in his own words, he is nothing more than “a rich man’s son when you really get to the heart of things.” “Simco,” as he is nicknamed, admits that the “current set-up certainly isn’t very fair.” The advantages that his peers have been afforded, that his contemporaries have grown accustomed to, need to be redistributed.

Around 11 years ago, Simchowitz set out to, in his words, “disrupt the establishment,” and began to purchase large quantities (and in most cases, entire collections) of art from artists Like Sterling Ruby, Petra Cortright, and Serge Attukwei Clottey, who questioned the status quo. By 2015, Simchowitz had built SimcosClub.com, an art-collecting, selling, and promoting website dedicated to successful, young, and emerging artists around the world. Simchowitz is not without his critics, though. He was famously dubbed “The Art World’s Patron Satan” by the New York Times back in 2014 and most who oppose him claim he preys on young artists who lack gallery representation. This stigma is one Simchowitz has worked hard to shake. Journalist Andrew Goldstein of New York Magazine, Artnet, and Artspace, one of his most vocal supporters, argues that Simcho is destabilizing outdated art-world archetypes that perpetuate dangerous myths about how art is distributed, displayed, and discussed.

When I went to interview Simchowitz at his home, his assistant answered the door. “You here for the interview?” he asked. I nodded, proceeding to follow him to the backyard complete with treehouse and pool. Simchowitz sat on a wooden bench, texting. “Thanks for taking the time to meet with me today,” I said, introducing myself. “Porter. Such a good name. It’s like a movie character. Let’s hop in the car and do the interview there. How does that sound?”

And so I caught up with Simchowitz while he rode around in his gray Porsche S.U.V., crossing errands off his list in Miracle Mile.

* * *

Michael Porter: You said that it’s “kind of random” when you find a new artist who intrigues you. Do you find that you are still hopeful when you go on studio visits?

Stefan Simchowitz: Well, I don’t ever do studio visits. Never. Ever. I use data and social media to find people. I need to see the artist and how he or she relates to the work. Studio visits are so work driven and I find that you can’t really get to know the artist. I need to know the artist outside of their environment because that is where that work is primarily going to live.

MP: Do you feel like you are going against the grain in your attempts to, as you say, “bring art to the masses”? And if so, why do you think that is?

SS: There is an institutionalized, established system or fabric in every social, political, economic, and cultural aspect of our lives today and it relies on this fabric which starts with the university. It is also which journals are writing about the artist. These things have become a beacon. They are selling art degrees, which are expensive to obtain and the school is making a lot of money from it. Anyone who has really been able to scale the enterprise of stealing money from poor people has had success in the education system. And the institutional establishment sort of upholds the educational one. They work in unison really, perpetuating this nearly unattainable lie. They tell you that you can move to the top of the art world in much the same way a lawyer ascends in his field. Art doesn’t work that way.

MP: How do you use social media to combat this sort of systemic thinking or way of art being substantiated?

SS: This idea has really been assaulted by the ability of artists to promote their work via Instagram and other outlets without obstructions from these institutions. They are supposed to be there to support the artist but, in reality, they are not. Most of the artists whom I work with I have met through social media, ironically. Zach Armstrong, I found on Instagram. Petra Cortright, I found on a website called Nasty Nets, which was prior to Facebook. So social media has been invaluable to me. The systematic art world is very disturbed by these various outlets for which people can not only consume and view art but also by how these tools can be used to discover and in some cases make art.

MP: So you rely heavily on data when finding new art and new artists?

SS: Data is the key. I research and I take the data I gather and feed it to people who buy for me because I can’t physically be there. I feel a bit like a drone operator in that sense because they aren’t giving the same precise data back to me. I think we fetishize this very cheesy experience of going to studio visits and the artist tells you how much they love art and how its changed their lives. This is a very Hollywood style of thinking.

I’m not saying you can’t find great art the traditional way. Look, that model is large and sophisticated and has been very, very successful for a very long time. But what I’m trying to get at, what is at the core of what I do and the way that I do it, is that “there isn’t just one way of doing things.”

MP: So, the magazines that promote artists, the galleries showing the art of artists — they work as obstacles to new art being shown and art being more accessible to people?

SS: Yes, because they operate not with the intent to show how you can achieve whatever it is that someone has achieved and then been deemed worthy by the art world, but what they actually accomplish in today’s world is to show how unattainable the goal really is. Social media breaks that wall. Exclusion is not what pushes art forward, it’s inclusion, 100% inclusion. And I mean this from a market perspective as well. I would rather sell 10 paintings for $100 than two paintings for $200 because those 10 paintings are 10 portals to new experiences. Who knows what effect those 10 paintings will have on the world when they go to whatever place they go to once they leave you. You’ve in essence created 10 portals for your work to travel through.

MP: What constitutes a good artist, and what do you think is the biggest roadblock to selling good art?

SS: The thing that makes a good artist is an adherence to an idea, a set of principles and disciplines which are attached and embedded within a unified aesthetic that can cross over into various mediums and media. Whether that be video, photography, sculpture, painting. It is a set of ideas that can be simple or complex, but the ideas must be expressed in a unified structure.

MP: How do you go about determining the price or value of a new artist’s work?

SS: That is a very, very tricky question to answer. There used to be this universally accepted sort of “minimum wage” for artwork. It was something like $1,200 for a painting and then it was $3,000, then four, now five. There is this weird baseline, it depends on volume as well. It’s like black magic in a sense. It’s sometimes right and sometimes wrong. It works and sometimes, it doesn’t.

MP: I watched the documentary The Art of Stefan Simchowitz (2017) in which you said something I thought was interesting with regards to your artists trusting you. You said: “You need a perfect combination of a lack of experience and an excess of faith.” What does that statement mean to you? How did you come to that idea?

SS: Experience is a word that is attributed to the establishment’s definition of going through what other people have gone through. So, you can be smart but not go through what someone else has gone through. Experience means that, to a large degree, you’re programmed by the establishment. Art requires faith. It is the secular religion of our time. Aesthetic practices are the practices of our time. They provide us meaning, they provide us identity and a vessel to represent our ideas. They’re like an old family crest — just in a different format. You know, street art, body art, tattooing — they function in this way.

MP: You mentioned to me that art can be decoration. Do you think decoration can be considered fine art?

SS: Absolutely. I think the fine art establishment has sort of diluted art and robbed it of its purpose. Art existing solely as decoration is bad, but that is not to say that decorative pieces cannot say something more, cannot be more than just a pretty thing. They have isolated the one function that art has. Art has become a financial instrument. Art becomes only two things: an asset or a decoration.

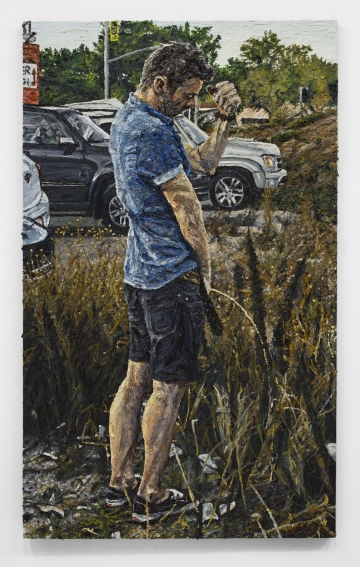

MP: You’re not just an art collector, you’re also a photographer. Do you still enjoy taking people’s pictures?

SS: I do, but I think people like to have their picture taken by people who aren’t themselves less and less as the years go by. I’ve been out and about shooting for whoever, Italian Vogue or someone else in that vein and I’ll literally be shooed away like a dog. It’s so strange. And you know, I’m never intrusive of spaces that aren’t mine but people really detest the photographer nowadays. I feel like the photographer has a bad stigma right now. Maybe it’s just me.

MP: Can you tell me what your earliest memory of art is?

SS: My earliest memory of art? I don’t know if I have that but I have one that functions like an aesthetic object to me. I remember having a dream that featured a concrete mixer, a woman in a red dress drinking a glass of lemonade. I think of it as an aesthetic experience. It was very structured. I also recall a picket fence. But when you say art memory, I don’t have this moment where I said: “ahhhh, what is art, or something kind of corny in that way.” I just have these images that I guess could be considered the beginning of my exploration of aesthetics.

MP: Have you always been aware of your privilege?

SS: Of course, I fucking went to Stanford and didn’t have to borrow the money to go!

MP: Where do you get that sense of awareness from?

SS: It’s not awareness, it’s a fact!

MP: Can you tell me a little bit about the competitive nature of the art world? You had a past life as a successful film producer. Do you think the art world is more cutthroat than the movie business?

SS: No, you can’t compare one industry to the other. That’s ludicrous. I could be a potato farmer and live across from a guy who does the same thing and we would be at each other’s throats just the same. I guarantee the breakfast cereal business is just like the art business. This idea that one is more competitive than the other is just simply untrue.

MP: What keeps you on the ground?

SS: Grounded? Who said I was grounded?

MP: You seem quite normal to me. I can’t quite marry the person in front of me to the person I read about online.

SS: You’re saying that everything you read might not be true? Imagine that.